As a bit of a mystery fan, it’s a little odd that Frogwares has flown under my radar up until now. Of the 14 games in their catalogue, 8 belong to the Sherlock Holmes franchise. One must assume you don’t make that many titles without learning a thing or two. There’s a lot to be excited about, seeing Frogwares further refine their prowess in adapting Holmes. Releasing later this year, I got a chance to check out a preview of Sherlock Holmes Chapter One, and it’s the way the game subverts the standard narrative that has me most intrigued.

Elementary – The Story Basics

As the name implies, Sherlock Holmes Chapter One is a prologue of sorts to the more common canon of Holmes. It explores Cordona, a pivotal location of Holme’s upbringing. This is not drawing on the traditional canon of Holmes, which gives a bit of creative license. After all, it’s very rare that this period of the great detective’s life is explored. However, we are not seeing the early childhood of our protagonist. Rather, this is more of a homecoming tour, with plenty of flashbacks to the formative years.

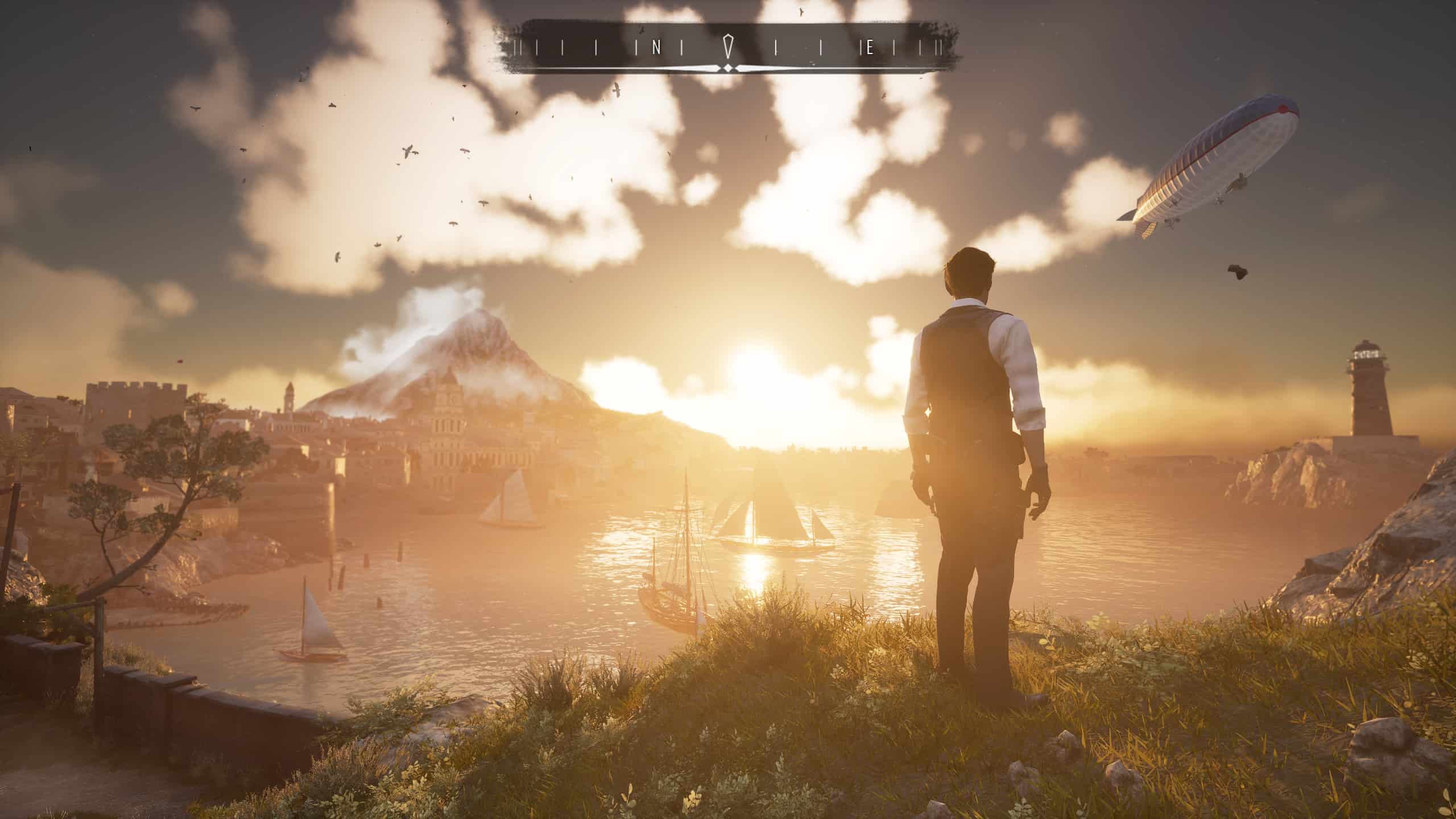

Cordona is an exquisite locale to centre our adventure upon. There is an impressive open-world that feels like it’s hitting a fairly good balance of elements essential to an open mystery. It is big enough to hide many secrets and requires careful navigation to find them. The map is split up into various sectors. Specifically, these sectors draw along different social lines. Grand Saray houses the rich upper crust, with wide streets of manors and estates. Scaladio is the bustling economic and administrative hub. Old City is where most of the Turkish natives live and thus has more of an Arabic inspired look to it. Such a large canvas allows for many game opportunities, but also for additional gameplay ideas, like the use of disguise to navigate the social atmosphere of Cordona’s sectors.

Partner in Crime – Regarding Jon

No discussion of Sherlock would be complete without introducing his partner, Jon. I must say that from scene one, I had an appreciation for the relationship between these characters. Traditionally, a Holmes and Watson pairing is often played as this classic “odd couple”, the eccentric and brilliant butting up against the diplomatic and straightlaced. Sherlock Holmes Chapter One, perhaps in its more youthful presentation, has a much more amicable bond. Our pair have an element of opposing strengths, but play more as halves of a whole. The differences are not points of conflict, but areas in which each can chastise and tease the other. They feel more like actual partners and friends than many versions I have seen before. It makes me curious to learn more about their shared past.

“Traditionally a Holmes and Watson pairing is often played as this classic “odd couple”… Sherlock Holmes Chapter One… has a much more amicable bond.”

There are a few ways this relationship is brought across. The first is the banter that makes up a large part of their dialogue. The writing is fairly good, there’s a solid back-and-forth, and the occasional off-kilter line feels appropriate as a text of its time. Another aspect is mini-cases referred to as “Cordona Stories”. These are pretty simplistic outings, using the concentration mechanic (i.e. the “Detective Vision”) to stage a short walking simulator flashback story. All of these follow little stories that explore Sherlock and Jon’s relationship.

Of course, it would be a glaring omission to not address the mysteries themselves. There’s a bit of a tiered system of the mysteries on display. There is one large mystery that acts as a bit of a framing narrative if you will, a big set of questions that seem poised to encapsulate the entire campaign. It touches all reaches of Cordona it seems. Just below that top tier is the “cases”. If you’ve played any 5 case games, Phoenix Wright, CSI, or other Sherlock games for that matter, this is what you’re probably expecting. They’re bigger cases, looking at a few suspects with a couple of scenes to run a magnifying glass over.

The Game is Afoot – How Holmes Does Things Differently

In Sherlock Holmes Chapter One, the inventory system is run a little differently. Objects you amass are collected in the case file system. Instead of the bottomless bag of holding, the case file system is built more as a collection of strings waiting to be tied up. Each object represents a clue of some kind, be it a physical item, a task, a location to search, a conversation topic, or so on. It renders the inventory as a more in-depth almanac of any given case. At any time you can pause and review the various elements of the case you have uncovered. Alternatively, peruse icons that form your to-do list, to find your next step forward. The other benefit of this system is it allows you to keep your mysteries separated. If you find a key location in your side case, for example, you can mark it on the map as being important to that case. Should you move on to other mysteries, it will clear out these waypoints from the map. It makes it really easy to jump back into the game with minimal friction.

One part of this whole compartmentalising of the game is about focussing on the right things at the right time. The game in this place has “pinned evidence”. I’m not entirely sure how to feel about this mechanic. It’s exceedingly important in gameplay, but it didn’t fully come across in the tutorial. I refer to it as “focus” because that’s a bit of a better framing of it. The game has a bit of an abstract description along the lines of “pinning evidence puts it up in the corner and it’s important when searching and talking to people”. It describes the mechanic, but it divorces it from the kind of language we use when describing actions in the real world.

I was caught off-guard by how pervasive the pinned evidence system is. Walk up to a person in the open world and click, and you are unable to interact. Pin evidence and all of a sudden your powers of speech are returned. In most games, you walk up to someone and then ask them if they know where city hall is. Chapter One inverts this, you pin the idea “I need to go to the town hall”, and then ask people if they know about it. Perhaps it’s a cunning way to avoid programming unnecessary chatter, but it’s not like it’s intuitive. Most people aren’t walking around with sandwich boards saying “where is the toilet?”. Overall, the system isn’t bad, but it’s not natural either. The explanation needs work to drive home the importance of it a little better.

Let’s consider another example of Frogwares leaving players to work things out: navigation. Like Sinking City before it, Sherlock Holmes Chapter One has no objective markers. If you want to find your way to a place, you need to get your map out. It’s a nice touch because it trains you to actually parse through information, and pore over the game map to locate the next scene. Similarly, other suggestions about evidence are a bit general such as search this area or talk to a key witness. Of course, some are particular to the lore of Holmes. Buying clothes and cosmetics can allow Sherlock to disguise himself, allowing passage into restricted areas or questioning passers-by. Concentration is Chapter One’s “Detective Vision”, which allows deduction of clues and tracking people.

“Chapter One is all about how you choose to interpret what’s in front of you”

All this is in service of the case, and with it, Sherlock’s famous deductions, housed within his “Mind Palace”. All these pieces of evidence are of little consequence if not pieced into theories. When you find a key clue, you can start to pair clues up. For example, a suspect claims that they spent an hour elsewhere away from the victim. This could pair up with some account verifying the claim. However, some deductions are less straightforward. If the account is less definitive, say, they were there for 30 minutes only, that allows for interpretation. Does this account suggest that a third party could have committed the crime in this window? Or does it serve to illustrate an untrustworthy alibi? Choices like these are totally reversible, mind you, but one way or another, the choices that are active impact the connecting deductions. Only with enough connections can you start to piece together your theory of who the culprit is. In this way, Chapter One is all about how you choose to interpret what’s in front of you.

Red Herrings – Vestigial Gameplay Elements

It’s not all a slam dunk, combat for one is a bit of a chore. If Sinking City, and for that matter Murdered: Soul Suspect, has taught me anything, it’s that combining combat and mystery solving is at best a challenging undertaking, and at worst a recipe for disaster. Makes sense I suppose, there isn’t a lot of intersection in the actions of a detective and a gunslinger. Of course, this is Holmes, so it comes down to his ability to analyse becoming bullet time, which then allows for fancy fireworks. Strip them of armour, and then shoot something that will stun them (or if you rather, discombobulate) so you can swoop in for an arrest. The first problem is that this is kind of ridiculous. This is a mode where you are asked to shoot off face armour. You know what usually happens if you are shooting directly at a person’s face, right?

It feels like a slog to do combat, and it feels like the devs feel the same. Each skirmish has a little loading screen. We get a brief cinematic in the little alcove filled with chest-high detritus. Detritus, mind you, that is absent from the rest of the streets of Cordona. It truly feels like we’re shutting down our detective game and booting up a janky third-person shooter for no reason. I honestly don’t get it. It feels like an ill-conceived “insert drama here” move. It speaks to some kind of insecurity, or focus-group demand, that has no real place in the final product. The kindest thing I can say about the fighting is that it is a completely vestigial part of the experience. In fact, whilst this was not made obvious to me whilst playing, in the difficulty options you can disable combat in its entirety. I, for one, am thankful.

On the subject of vestigial gameplay elements, let’s talk about Jon. Of course, as I said, as a character I generally like Jon. Here’s the thing: I like cutscene Jon, the charismatic, intriguing partner that makes for a good foil for Holmes. Leave the cutscene, however, and all depth vanishes, leaving behind a bafflingly drab character. This may be a case of limited resources. Like many of the open world characters, there isn’t a lot of talking outside of cutscenes. Even the interrogations can feel a little lacking in meat. Jon himself will generally just parrot back a single line if you move to interact with him. Of course, drastically reducing his voice lines puts him in danger of seeming like a lifeless character. To solve this problem, we have the classic method to communicate a story: a diary entry.

The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes – Telling Stories through Text

I must say, I’m really starting to dislike the “random bit of text” method of storytelling. Be it diary entries, random letters, documents or audio logs, they are really pervasive. It was barely two weeks ago that in a recent review I had similar grievances. In some cases, it creates this frustrating hurdle to uncovering the entire story. In others, it creates this weird “opt-in” feeling that feels akin to having the cake and eating it too. In the case of Sherlock Holmes Chapter One, not unlike the previous review, it just feels unnecessary.

One should expect some reading in a mystery game, but not all the text is worth writing. The case file, for example, has a good deal of information to pore over. Fair enough, we need all the data we can get to solve a case. I can also see the value in getting to review past cases and the little summaries of the memories we’ve uncovered. Even if there ends up being no great mystery behind them, there is a lot of fun in speculating and forming theories. Why bother playing mystery games if not to deduct and theorise? The bigger issue I have is that, to put it bluntly, I don’t need Jon’s input.

Throughout the game, Jon writes about your time together in his diary. Specifically, he will write about how your actions positively and negatively influence your relationship. I suspect Jon’s relationship with Sherlock will have some kind of bearing on the wider story. Perhaps there is some moral choice ending that takes your friendship into account.

“To put it bluntly, I don’t need Jon’s input.”

The issue I have with Jon’s Diary is that it also bears out Jon’s grievances. This allows the diary to be a nagging list of complaints about you failing certain tasks. This is in a game, may I remind you, that is, compared to other games, somewhat vague in its instructions. For example, if I had to find an area with no real instructions, I might ask around. Generally, this wouldn’t help at which point Jon would pipe up that I should stop bothering people, a sentiment reflected in his latest diary entry. On another occasion, I searched in vain through an archive. To cut a long story short, I found out sometime later that there are multiple archives, I was in the wrong one. Upon exiting I had dozens of little thumbs down diary entries on the notifications. The worst of all is probably the ones calling me some deranged killer after combat. I fend off a dozen or so maniacs with shotguns, and among all the swanning about doing stun arrests, I accidentally kill one. Yes, that is a shame that human life was snuffed out, but I’d rather not have this mess of a combat end with hand-wringing from the peanut gallery.

Not-so-Hardboiled – Is Sherlock Holmes Chapter One too easy?

I suppose in many ways this represents the frustrating point of Sherlock Holmes Chapter One. Because the combat, and dealing with Jon’s annoyance, mirrors the main roadblock in getting through the game quickly. Perhaps even too quickly. See Sherlock Holmes is a well-oiled machine at this point. There’s only so many games in the exact same style one can make before you make things as efficient as possible. I suppose the problem is that there are rather few true puzzles here. Find the place of something on a map, walk to the place, find all the evidence. It comes across as a bit too straightforward sometimes. In fact, in some cases, I took longer to find things because I assumed that they were going to be harder than they wound up being. I’d assume the last line of a riddle indicated some far off final step when seemingly it existed solely to fill out a rhyme scheme. So if there is a challenge, it’s often understanding where you lost the thread.

Even then, the lost thread is not really a puzzle challenge. In some cases, I did all the work I needed but fell short arbitrarily. In one instance, I found the illegal goods someone was smuggling. Until I pointed at the box they were in, however, the game refused to grant progression. Some inspections took some time to find the final clue. I’d have the wrong thing pinned and be meandering for some time. These are the kind of really low hurdles I had to clear. When puzzles are properly introduced, they have a very escape room quality, clever but straightforward clues. There are even very explicit puzzle mechanics, albeit really simple ones. They are too few and far between to fully whet my appetite.

“There’s only so many games in the exact same style one can make before you make things as efficient as possible…”

For the sake of thoroughness, I did, when informed of its existence, try out the harder difficulty. I like that it exists, I similarly like the “Mycroft” mode that allows for customisation. Does it address my issues? Somewhat. I think the issues have been a bit too baked into the design document to really be undone with difficulty customisation. The “hard mode” removes some alerts, doesn’t give you interactable icons and doesn’t indicate when an area has been fully gone over for clues. It’s removing helpful indicators of progress. In a sense, it isn’t a harder game, but a less easy one. In some circumstances, a harder puzzle actually helps make you earn some information. Chemical analysis is a proper puzzle now. In all other respects, it’s kind of just an annoyance.

Is there any issue with the game being too easy? For my taste, I can’t see it destroying the game. After all, my interest lies primarily in the story. Invariably, I’m drawn in by the many little mysteries. A lower difficulty reduces the friction, allowing an easy glide through the suspenseful plot. In fact, I’d rather it be a little too easy than too hard. Furthermore, I have played only the first slice, and I predict, like many other multi-case mysteries, that the complexity will continue ramping upward. However, difficulty settings aside, the mechanics don’t feel like they will allow for the kind of challenge I want from a mystery title. As such I can only hope that the mysteries, in and of themselves, are enough to satiate me through the campaign.

Sherlock Holmes Chapter One is coming to PC, PS5 and Xbox Series X on November 16, with PS4 & Xbox One versions slated to a later date.