A year in, Mihoyo’s Genshin Impact is a world of contrasts. The anime-like RPG manages to sometimes feel both bland and inspired in its design, the gameplay loop in parts tedious but addictive as a whole, the story occasionally under-realised yet oftentimes compelling, and (arguably its selling point) the characters in some ways not fully utilised, yet undeniably charming.

After picking up over 38 million players in its first week and continuing to grow since then, it’s clear that Genshin Impact has both widespread appeal and access. But the most Tweeted-about game in 2021 somehow still manages to feel underrated or at least under-reviewed, with gameplay analysis far overshadowed by discussions of its gacha monetisation. Gliding through the world of Teyvat after its anniversary, it’s clear that the game feels much fuller than it did in 2020, but I’m not sure that it feels complete. When we look to the future, what should we expect from Genshin Impact? What should we hope for? And how much of a difference is there between the two?

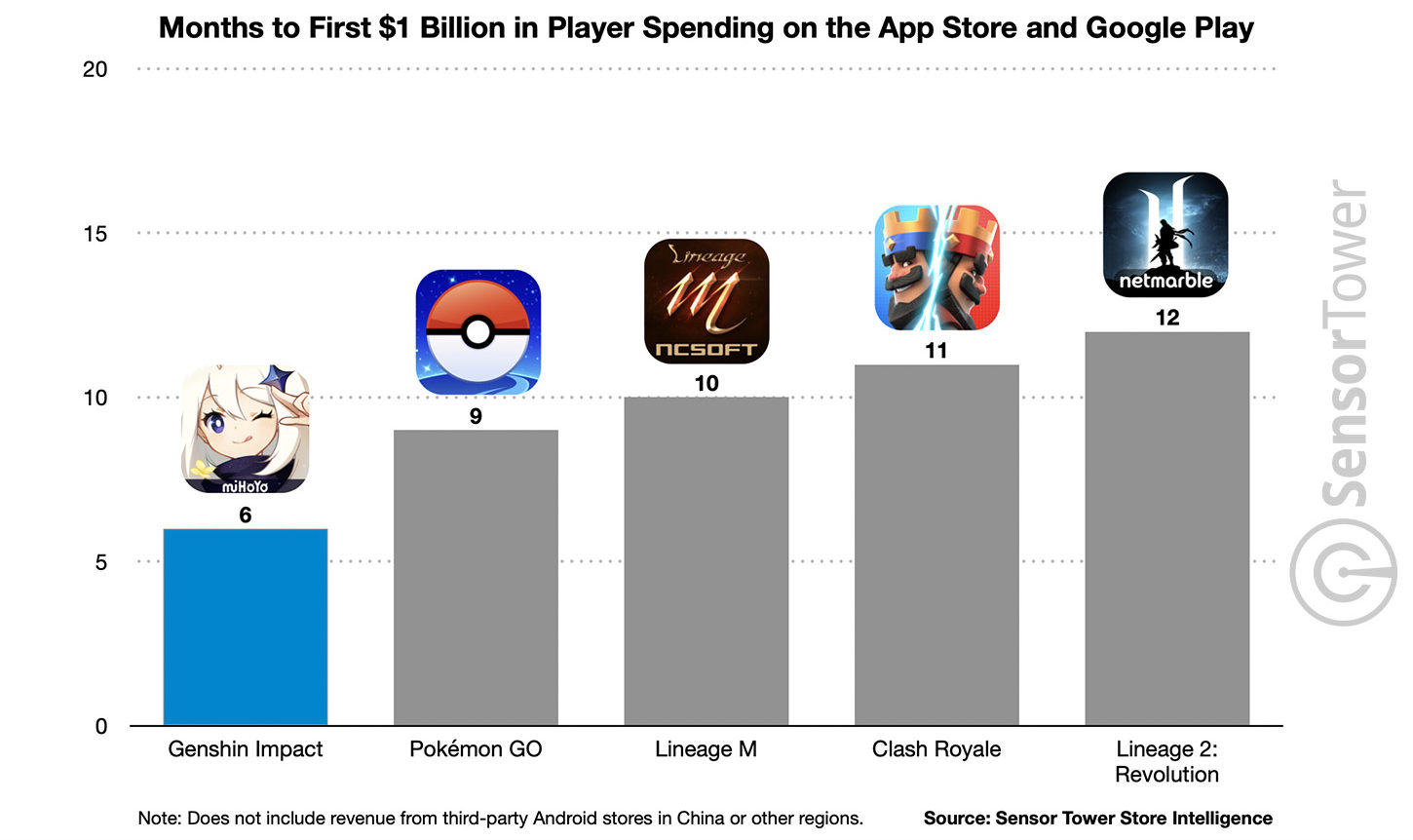

After being founded by three Shanghai-based University students in 2011, it’s incredible to look back on Mihoyo’s latest game’s achievements, ten years and hundreds of employees later. The fastest app to hit the one-billion-dollar milestone on Google Play, achieved in just under six months after release, making it an unsurprising Best Game of the Year winner in 2020. Genshin also took home Game of the Year for iPhones in the same year and won the Visuals and Graphics category of the Apple Design Awards in 2021. The games’ composer Yu-peng Chen has also nabbed Video Game Music Online’s ‘Outstanding Artist—Newcomer’ award for his work, with an orchestral soundtrack featuring performances from various international cities’ Symphony Orchestras. None of this accounting for its PC and PS5 success, with some sites estimating that Genshin’s player base has continued to grow throughout the year with Smash Bros-esque character crossovers being greenlighted by Sony. It’s also been reported that a Switch port of the game is supposedly in development.

Despite the accolades, in the almost a year I’ve been playing Genshin Impact, I’ve developed a kind of pre-emptive self-deprecation about it. The game’s notoriety in the west as an anime-inspired, gacha, and (perhaps most painfully) primarily mobile game means that despite its popularity, the game feels strangely niche.

But in some ways, the game itself has also conditioned me to see it, and play it, in a particular way. I find that my experience of what the game is is in constant flux—what is it really like to play? In some ways, there are two ‘games’ in Genshin Impact, and some days when I log in, I’m logging in to play one in particular. On other days I’m guided towards another.

Welcome to the world

The first game is the one we’re introduced to at the beginning. Our protagonist is either Aether or Lumine, one of two twins stranded in Teyvat and separated from their sibling by a mysterious god. You, along with a mysterious companion-slash-anime-style-mascot named Paimon, go on a quest to look for your estranged brother or sister, hoping to find help or guidance from one of the seven deities of the world, called Archons. Each Archon rules a particular nation and element of Teyvat, and the game begins in Mondstadt, the nation of wind.

While the world is unfamiliar to the main character, it’s likely familiar to the player. The game’s designers acknowledge the heavy influence Breath of the Wild had on their design and the similarities in direction in the preliminary section of the game are unsubtle to say the least. On leaving the introductory beach where the player learns basic movement, we arrive at an outcrop that lets us look out into Mondstadt—a moment so similar to Link’s awakening on The Great Plateau that I have to believe it’s intended as a homage. But while Genshin fails to recreate the magic of Zelda, it does manage to cast a different spell.

“But while Genshin fails to recreate the magic of Zelda, it does manage to cast a different spell… The graphical style fits Teyvat wonderfully.”

The soft pastel, cell-shaded anime style enables Genshin to be played on PC, PlayStation, or mobile phone and tablet, with little of the game’s graphical tone and feel being lost as you scale down the power of your device. The fact that such a huge world can be explored in even some older smartphones is impressive in itself, but as you progress further through the game and discover the various environments they’ve built, it’s clear that Mihoyo’s team didn’t choose the style purely for its utility. The graphical style fits Teyvat wonderfully.

The world design is relatively simple in Mondstadt, the European-inspired first region of the game. We’re treated to a very typical fantasy setting—lush green woodland surrounding small townships, ruined outposts and of course, a bustling capital complete with bards, knights, and a Euro-centric theme of ‘freedom.’ The choice to choose a European-style fantasy setting initially seems odd, given the background of the game’s designers and the relative quality of the Asian-inspired regions, but it makes sense given the way that Euro-Medieval inspired fantasy has become such a cultural touchstone across the whole world. In playing the opening of the game again, I was reminded of a strange sense of familiarity I felt towards the setting. Whether in World of Warcraft’s Goldshire, or Wheel of Time’s Emond’s Field, or Re:Zero’s Lugunica, there’s a simplicity to the initial region that is comforting. Ah, you think, this is a fantasy world.

The game’s physics engine is similarly basic, and the way to interact with the world is usually obvious. There are monuments that react to particular elements; wind currents that propel you into the air, spirits that you follow to their particular shrines, and chests that unlock once you’ve defeated nearby mobs.

Exploration is achieved through a mixture of climbing, gliding, running, and swimming, all of which require a mild level of stamina management. And the peaks, ruins, and cities you travel to are easily distinguished in the distance. But there’s something to be said for the quick hits of satisfaction the game gives you by pumping the world full of chests, mob encounters, and small puzzles. These obstacles in the overworld are rarely difficult, but it’s hard to feel that they need to be all the time—in many ways they exist to engage the player and encourage exploring, to ensure that what feels open doesn’t also feel empty. Even without the chests and hidden treasures, there’s a definite satisfaction to climbing to the top of a mountain if only to survey the wonderful world around you, and you can easily spend hours ignoring the main quest to investigate some distant peak on the horizon. One of the most powerful moments of the game is crossing over into the second region, Liyue, to Mondstadt’s south. To finish your time in Mondstadt and be confronted with a new, even larger continent to explore makes the world of Genshin Impact feel truly immense.

Liyue, the Chinese-inspired nation of earth is an improvement on Mondstadt in a variety of ways. The land itself is larger and has more variety to it, the quests make better use of the varied environments, and the location of puzzles and treasures feels more crafted. There are tranquil turquoise pools flooding old ruins, towering spire-like mountains inspired by the landscape of Zhangjiajie, idyllic rice-terraced mountain-side townships, and of course the grandiose port of Liyue, the City of Contracts. The culture of the region feels more distinct and developed. A theme of relationships and collaboration pervades both the main and side quests in a way that’s far more directed and intentional than Mondstadt’s ‘freedom.’

By Inazuma, the Japanese-inspired third region released in July of 2021, it’s clear that the designers have come into their own and will likely continue to improve. The shifts in the environmental tone are more pronounced, and areas even within a region feel more distinct and engaging. Mondstadt and Liyue are distinct, yet similar, perhaps necessitated by their geographical connection. But separated from them by sea, the string of islands that make up Inazuma are a different beast. A boat mechanic—while still rough around the edges—enables the individual islands to feel more distinguished from each other, and the hints of water-based encounters that we’re given suggest that aquatic terrain design is something Mihoyo wants to continue to explore.

Meanwhile, an increased emphasis on verticality and a refining of the game’s deployment of environmental hazards make exploring far more complex but also far more rewarding. The puzzles of the landscape are more nuanced and interconnected. The scale of certain challenges and side-quests is increased, and their resolution brings with it more far-reaching effects: a cavern opening up; a lake draining of water and revealing a dungeon underneath; the dissipation of a fog of dangerous radiation; an island forming in the sky. Despite the increased difficulty, there remains a wealth of simpler puzzles and accessible chests to keep the hits of dopamine coming. Of course, the joy of exploration persists and newer ways to get around keep things interesting. That’s not to say that every piece of explorative content in Genshin Impact lands, but it’s clear that Mihoyo intends to continue to iterate and improve on a solid formula.

Foes familiar and fantastical

Combat is another avenue in which Genshin provides us with an experience that is simple but satisfying. The player controls a party of four characters that they can switch between. The on-field character fights in real-time, using basic or charged weapon attacks which can be chained together, and weaving in elemental skills and burst abilities while trying to dodge attacks or stagger enemies. Switches between characters are instant—the game introduces a layer of strategy in the way that certain elements work together, and combining multiple skills is an important way to take down harder enemies. While the overworld and story content is quite forgiving, for the late-game Abyss, Boss or Domain farming, understanding team compositions and elemental reactions becomes increasingly important.

The earlier mob designs in Mondstadt and Liyue encompass a quirky variety that slowly diversifies over the course of the continent. Aesthetically the enemies fall into the same hat that games like Zelda and Dragon Quest draw theirs from: fun, rather than menacing. Their kits are generally straightforward too—melee enemies that charge at you or ranged enemies that shoot at you, sometimes incorporating shields or various abilities with radius markings that generally give you a generous amount of reaction time that are easy to handle given the game’s similarly generous invulnerability frames. Adventure ranks give the player the opportunity to scale the level of their world up or down, but even on the highest difficulties, most of both Mondstadt and Liyue is straightforward for even a casual player to make it through.

While aesthetically coherent with those before them, the mob behaviours in Inazuma are at times challenging, and sometimes frustrating. Not only do they have higher scaling damage and health totals, but they also employ a greater range of movement abilities. These combined with some improved crowd-control resistance means Inazuman mobs require more precision to deal with—movement is no longer reserved to be used defensively, and closing the gap or manoeuvring into a more advantageous area (away from deep pools of water against electric and ice enemies for instance) is another skill-check the game has incorporated. Newer mobs also seem aimed at upsetting the community’s tier list of characters, with bleed damage to encourage the use of healers and floating enemies to promote the use of archers and casters. Boss fights have also become dramatically more complex, though the reliance on occasionally unclear invulnerability phases is a consistent source of frustration for a lot of players.

Complementary sides

On top of the basic mix of exploration and combat, Genshin has taken to adding in other mini-games and side activities, sometimes temporarily, and sometimes permanent.

A role as a home and realm designer is the most stable and impressive side-gig that our protagonist takes on. Through the power of a magical teapot, you’re able to construct an entire landscape, full of decorations and furnishings in which you’re also able to invite the characters you’ve collected. The builder interface is surprisingly robust, and designer-type players will undoubtedly enjoy the outlet that feels sort of like an Animal Crossing lite, with the ‘lite’ only becoming less pronounced as time goes on. There are even players who have made use of the unintended interactions between landscape and building tiles to create amazingly layered constructions.

Music and rhythm games are a reoccurring event-based game type, and Mihoyo has taken to rewarding the completion of event quests with unique instruments that can be used to play music in-game. Alongside these, Mihoyo has a roster of developing mini-games including, amongst others: Tower Defenses, Archery Ranges, Gliding/Flying, Obstacle Courses, and my personal favourite, multiplayer Hide-and-Seeks.

Music

While not perfect, Genshin weaves its gameplay features together into a cohesive package by use of three key elements: Music, story, and character.

Music is the most consistent strength of Genshin Impact. It cannot be overstated how integral Yu-Peng Chen’s compositions are to the mood and feel of the game. The wonderfully enticing fantasy-feel of my beginnings in Mondstadt can easily be attributed in part (in very large part) to tracks like Mondstadt Starlit and Tender Strength. Even stages of the game that can feel relatively under-cooked in their design and experience, the Dragonspine region for example, are carried by beautiful melodies like Glistening Shards that are somehow noticeably entrancing without being distracting. What separates his work from that of other video game composers is the way that musical themes and motifs recur—sometimes quite subtly—across various pieces, lending the body of work both a cohesive and familiar feel. His instrumentation also lends each region a particular musical aesthetic and character, with each region not only performed by their corresponding real-world influence’s Symphony Orchestra—Mondstadt’s OST is performed by the London Symphony Orchestra; Liyue’s by the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra; Inazuma’s by the Toyko Symphony Orchestra—but also drawing on traditional instrumentation.

The compositions found within Genshin Impact are not only thematically inspired but also technically skilful, having accrued a variety of awards since release and even being featured on BBC Radio’s Classic FM. And it’s clear that Mihoyo values the power of the Genshin soundtrack, given their consistent featuring of performances in their media, most recently including an almost two-hour concert in celebration of Genshin’s anniversary. Chen’s work and the performance of the musicians he collaborates with remind us that video games often include layers of artistic expression, pieces of which can stand proudly on their own.

Story

Story is a less consistent but equally potent tool in Genshin’s kit. Stylistically, questing leans heavily into character development, and as a result, are often heavy on dialogue and feel more focused on engaging the player emotionally rather than providing them with complex problems to solve. When this fails to land, the game’s pacing feels stilted, and the interactions we’re served feel tedious and underwhelming. Side characters are sometimes introduced and developed primarily within a questline, and perhaps the weakest aspect of Genshin’s story-driven quest focus is the lack of lasting effects that carry on into the world after the quest is done. Quests can sometimes feel insular, emotionally resonant maybe, but prevented from feeling truly impactful by the lack of meta-narrative outcomes.

The main quest and through-line that we have is initially crafted as a sort of by-the-books isekai. Isekai, or literally ‘different world’ in Japanese, refers to a genre of stories (typically anime) that revolve around a protagonist transported to another world. While the genre encompasses a broad variety of works, in anime in particular it has come to be associated with a variety of tropes. The gist of an isekai story is that while initially the protagonist pursues a particular goal—often trying to ‘just survive,’ focus on getting home, or in some cases find a partner or friend—they eventually find themselves forming connections within this ‘different world,’ and become invested in it (along with the viewer).

In Genshin, the protagonist initially serves as a crude invitation into the world of the game. In my case, Aether’s search for his sister felt like a barebones attempt at crafting a driving, overarching plot that enabled him to meet and interact with what initially seemed the ‘real’ appeal of the game—the host of characters and their stories. This was reinforced by his sparsely voiced dialogue, generally muted reactions to occurrences in the world, and the relative infrequency of him making progress in finding his sister. In some ways, the voiceless protagonist felt like a carry-over from the Breath of the Wild inspiration the designers had referenced. But this style of characterisation felt somewhat awkward during the stories as many of the interactions between Aether and the other characters were facilitated by Paimon. And Genshin’s world is far more densely inhabited than that of most Zelda games, not speaking just feels off, rude even. But Genshin’s writers seem undecided on this, as more recent story quests have shifted to give the protagonist a stronger presence, and recent story quests have provided Aether with more lines of dialogue and much stronger emotional responses.

“But the main reason we care about the outcomes of the quests and their thematic expressions is obvious. In true isekai fashion, the appeal of this ‘different world’ depends on the characters that live in it.”

The evocative power of the quests is drawn from the relationships of characters in their particular region and corresponding Act. While at times feeling under-developed, the Genshin writers manage to evoke a strong sense of the theme and culture of each region, with this emphasis only improving over time, with Inazuma’s ‘Eternity’ being channelled beautifully into its quests.

The sense of culture, particularly Asian culture, that permeates the Genshin world is no small draw either—as a Western-born Asian, there’s something validating about playing through events like the Lantern Rite and Moonchase Festivals, both respectfully taking inspiration from major Chinese festivals.

But the main reason we care about the outcomes of the quests and their thematic expressions is obvious. In true isekai fashion, the appeal of this ‘different world’ depends on the characters that live in it.

Characters

In case it wasn’t obvious already, Genshin’s style of writing is heavily influenced by anime, and its character writing in particular comes with all the sensibilities, the flaws and the charms, of anime writing.

Put simply, they are all unbelievably sincere. Amber’s desire to uphold the honour of the knights is uncompromising, Lisa’s interest in knowledge and belief in the sacredness of her books is unflinching, Jean’s continuous neglect of herself in favour of her duties is ridiculous, Diluc’s distrust for the knights is blatant, and Kaeya is obviously, obviously up to something. The characters aren’t one-dimensional, but they hold so tightly to their ideals that they often feel fantastical on an emotional level. And it works.

In a world saturated with gritty media and an obsession with amoral characters, Genshin is a refreshing reminder that idealism can be not only appealing but engaging. It’s not that the characters have no conflict or uncertainty, but with the simple purity of fairy-tale and heroes, they manage to act anyway, and there’s something pure about watching and playing them.

The Genshin characters are also some of the most uniquely designed characters in video games. While the diversity of the character models is somewhat lacking (playable characters are all slender at the time of writing, and there are only two characters with darker skin tone), character costume designs and animations both do a lot of work to add to their personalities—and both are things that Mihoyo continues to improve at.

It goes without saying that the voice acting, particularly in Chinese and Japanese, is wonderfully done—with the latter employing the use of a seasoned, frankly star-studded (often to the point of bringing fanbases of their own) cast of voice actors and actresses including Miyuka Sawashiro (Hunter x Hunter), Rie Takahashi (Re:Zero), Yoshitsugu Matsuoka (Sword Art: Online) and Masakazu Morita (Bleach).

A common complaint is that the Genshin world, while populated, is strangely missing its playable characters. Though Mihoyo continues to work on this—increasing their appearances in quests, allowing them to exist inside the player’s teapot realm, and unlocking all of them for play in more events—it’s undeniably jarring at times that the characters we grow so familiar with are strangely lacking in the overworld. This absence also has effects on the resonance of the quests, we often don’t see those who are most affected by the outcomes of our questing. The change the protagonist makes in the world is hidden. In many ways, the only way we get to experience them, outside of their specific quests, is by playing as them. And doing that involves something else entirely.

The other side of the coin

This is the second game in Genshin Impact that we’re introduced to, gacha. For those unfamiliar, gacha refers to the mechanics of gachapon—a variety of vending machines that dispense toys inside capsules, popular in Japan and other Asian countries. The machine displays potential prizes, but the contents of the capsules are essentially randomised. In video games, this translates to what are effectively a form of loot box.

In Genshin Impact, the game gives you the opportunity to ‘wish’ on a certain banner with a chance of obtaining a character and an even smaller chance of obtaining a rare character. To further complicate things, weapons are also available on the banner in a variety of rarities, and duplicates of either weapons or characters can be used to upgrade those prizes. Weapons can be refined up to five times. Characters can be given ‘constellations’ which allow them to be upgraded six times. The workings of the system are further obfuscated by wishes being purchased by using primogems. Primogems are obtainable in varying amounts by finishing questlines, completing achievements, events, daily tasks, and most importantly, by paying real money.

It’s important to note that for the most part, in a practical sense, what separates the two rarities of characters—four and five stars—is just that, their rarity. Five-stars are undoubtedly stronger in most cases relative to their counterpart four-stars in similar roles, but the rarity of five-stars means that upgrading them is out of reach for the vast majority of players. Whereas over time, players will almost unavoidably accumulate duplicate four-star characters, putting them at similar power levels on average (with some exceptions). The game also gifts the player several free characters as part of the main quest, as well as alternating between providing the player with either a free character or weapon during larger events. Notably, one of the most powerful characters for end-game content (jokingly referred to as one of the ‘six-star’ characters), Xiangling, is given to the player early on into the game. The provided characters are more than enough to handle the entirety of the game’s content at any level or difficulty setting. There are even a host of streamers who create content showcasing how to clear the Abyss (the theoretical end game) having never wished. All this to say, in terms of story and game content, Genshin does still earn its ‘free to play’ title.

But unfortunately, that title largely ignores how human psychology works. Whether through a desire to collect, FOMO, or simply a strong attachment to a particular character, players are encouraged to wish. This combined with the fact that a character banner (meaning increased rates for one five-star and three four-star characters at a time) only lasts three weeks, means that players are pressured to accrue a certain amount of primogems by a particular time to obtain the character they want.

Primogems are obtainable in relatively high quantities by playing the game, completing events, and exploring to find collectibles. Primogem rewards are particularly frequent as you complete the main quests for the first time and rank up. But once those initial sources run out, there’s a shift in focus.

Over the course of a 30-day period, you can net yourself almost a wish a day, assuming you complete events, daily quests, and do decently in the abyss. For certain types of players, this is enough. At my current stage in the game, having acquired a few 5-star characters that I enjoy, my interest in the latest banners has noticeably waned. Primogems and wishes can pile up un-spent until (inevitably) a new character grabs my attention. But it would be dishonest to say that this is the reality for most players, and it would be dishonest to say that I’ve managed to maintain this outlook towards the game for the majority of the time I’ve been playing.

A different view

A day after Genshin Impact’s anniversary, it had dropped from a Google Play rating of over 4.5 to a modest 1.9.

The event running during the anniversary was the Moonchase Festival. It had a well-crafted story that provided tender moments (complete with voiced dialogue) for a variety of featured Liyue characters, and deepened pre-existing themes of thankfulness, remembrance, and history which, to me, felt like a nod towards the game’s one-year milestone.

Despite all this, player outrage boiled over due to the lack of primogems provided during the event, with a loud portion of the online fanbase suggesting that the event was a waste of time. There’s an expectation in gacha game communities that anniversaries are events that give the players relatively large amounts of either virtual currencies or pulls (wishes). The primogems awarded during the event, roughly the equivalent of 20 wishes, were simply not enough.

Even if players resist the urge to spend under the conditions of the game, the presence of a premium currency can and does warp their perspective. The player finds themselves funnelled towards what is effectively a primogem management game. How many gems do I need to save? And by when? These questions can, unchecked, commodify the entire gaming experience. This is also partially because Genshin’s only ‘endgame’ content, the Abyss, primarily rewards the player with primogems. And event rewards are generally similar, with the big draw for a lot of players being the primogem rewards for quest completion, as opposed to the experience of the quests themselves.

Genshin characters themselves are more thoroughly and critically evaluated by the community to determine their ‘worth.’ Recent Inazuman characters in particular, like Kazuha, Raiden, and Kokomi, caused community outrage due to being supposedly underpowered. Weeks after release, it became clear that Kazuha occupied his own niche and is often referred to as one of the most fun characters to play. Raiden’s ideal team compositions are still being theorycrafted, but it’s clear that she is more viable than initially suggested. And while Kokomi, as a healer, fits poorly into the current meta, it feels likely that as newer enemies are added, her worth will rise.

The currency of time

How should we assign value to a game and its content? As I’ve gotten older and as video games—and theoretically, the hours I spend on them—have become more expensive, I’ve found myself doing a familiar sort of mental arithmetic. Is the metric of dollars spent to time played an effective measure of a game’s value? But how does this factor in grind? How much grind is too much? In my opinion, a good game takes your time and your effort and your imagination and performs an alchemy that makes the sacrifice of those things feel worthwhile.

Genshin is truly asking for your time. The real-time gated primogem economy combined with a mixture of the relatively unobtrusive energy system and a robust fortnightly event schedule means that to get the absolute most out of the game, you’ll have to be committed. On the one hand, this habit of short gaming sessions does make the game manageable, and stops me from drawn out binges—but on the other, it’s an obvious ploy to create more frequent play habits over a longer term, partially driven by FOMO. If you don’t use your energy today, it’s wasted. If you don’t play the event sometime during those two weeks, you’ve missed out.

In a way, my investment in Genshin Impact feels like my experience watching TV shows and reading comics almost 10 years ago. A medium that encourages and expects me to show up week after week to stay up to date. But I can’t say the experience is an entirely negative one, there’s a comfortable familiarity and excitement to logging in and seeing that a new event has begun, and with it the return or addition of mini-games and quest lines. And there’s a definite satisfaction to crafting a team of characters I enjoy. When I said that on particular days I was logging in to play one particular Genshin, sometimes the side I was choosing to play was the gacha. I wanted to do my dailies, smash through the abyss, and ‘earn’ my next character.

The base of Genshin Impact, that engaging ‘first game’, is a unique gaming experience that I can confidently recommend to anyone who’s a fan of the genres and media it draws inspiration from. But the ‘second game’ of Genshin continues to confuse me. Sometimes I find myself unsure of whether I’m playing or being played.

Into the future

The list of genres Genshin Impact occupies continues to grow: Anime RPG; Zelda-style Action-Adventurer; Social Sim; Farm Sim. And a year into the game, the amount of care put into certain aspects of the game gives me confidence that the game’s designers will continue to iterate and improve on the parts of the game I love.

But while the insane two billion dollars in sales they’ve achieved makes me believe that they’ll have more than enough resources to do so—the question of how that money was acquired concerns me. Not only because it represents a deeply cynical financial strategy for interacting with their fans, but because the game, and the community’s perception of it, is irrevocably altered by its existence.

In preparation for this reflection, I made a new account and played the game from the beginning. It was scary and confronting to, even temporarily, abandon the account that I had put time, effort, and yes, money into. But in doing so, I realised there was a gaming experience that I’d somehow lost track of in order to pursue something else.

It’s my hope that as time passes, Mihoyo puts less effort into making us forget how good their game can be.