Platforms:

Xbox One, PS4, PC, PS5, Xbox Series X|S

Released:

November 16, 2021

Publisher:

Frogwares

Developer:

Frogwares

In pop culture, few figures in literature compare to the influence of Sherlock Holmes. No matter their moniker, mystery games are no stranger to the great detective. Frogwares has been leading the charge when it comes to Sherlock Holmes games; the 13th and the latest entrant, Sherlock Holmes: Chapter One, delves into the early days of Holmes. This new entry into the series succeeds in story, gameplay and presentation, but rarely capitalises on them simultaneously.

This version of Sherlock picks up the story with our titular gentlemen as a young adult. Holmes has arrived upon Cordona, to lay flowers upon the grave of Violet Holmes, Sherlock’s mother, who died during Sherlock’s childhood. Soon this simple act of grief re-opens old wounds. Returning to Stonewood Manor, Sherlock is confronted with difficult questions: Is there an objective truth to be found?

It’s a curious theme to ponder in a mystery game, in both interpretations. Viewed as praise, the theme is a bold choice. Finding the truth is generally the whole point of a mystery game; your judgements add a wrinkle to this. The system suffers when the developers meet it halfway. Some cases have clear answers, and failure frustrates other characters. At times I had a sense that the game is having its cake and eating it too; it wants to berate me for being wrong, after assuring me that there are no wrong answers.

In the canon of Arthur Conan Doyle, details concerning Holmes’ childhood are sparse. Frogwares instead creates origin stories for the Sherlock canon. For example, Sherlock’s violin comes from a case on the island. The “Cordona tales” take the concept further, their sequences are long streams of exploring memories of those places. These are an oddity. In lieu of a mystery per se, the detective vision acts as the lens through which we can “take a walking sim down memory lane”. These are new tales from the developers, as a straight adaptation would be unwise – any fans of the books would know the answers. The stories and even the entire island of Cordona is a Frogwares invention.

Open world games can be a bit overdone, but Cordona succeeds as a densely packed world brimming with character. The districts are themselves marked divisions between the citizens of Cordona. There is a culture clash between the Turkish settlers and the British occupants. With the occupation, the Turkish population was relegated to the eastern island, a district called Old City, which maintains Islamic architecture. The further division follows class lines. Scaladio and Grand Saray have the central position, which is where power and money reside. Fittingly, your allies in the police, the local government and the tabloids, all operate here. Poorer districts, including Old City in the east, surround it. On the western island, the citizens live in poverty in the shadows of a now-defunct silver rush. This shantytown district is aptly named Miner’s End. Up north, a similar state of disrepair hangs over Silverton, a manufacturing district.

All these districts have discrepancies. The culture, the people, the architecture, all carry distinctions if you pay close attention. Generally the different types of people are handled fairly well. It does not shy from the ideologies of the past such as racism (if you consider it “the past” I suppose), rather than sanitising it. There’s also a bit of cross-dressing here too. Not sure if it deserves progressive brownie points here; the revelation is part of deduction, giving it a “ha I unearthed your deception”/clocking kind of vibe.

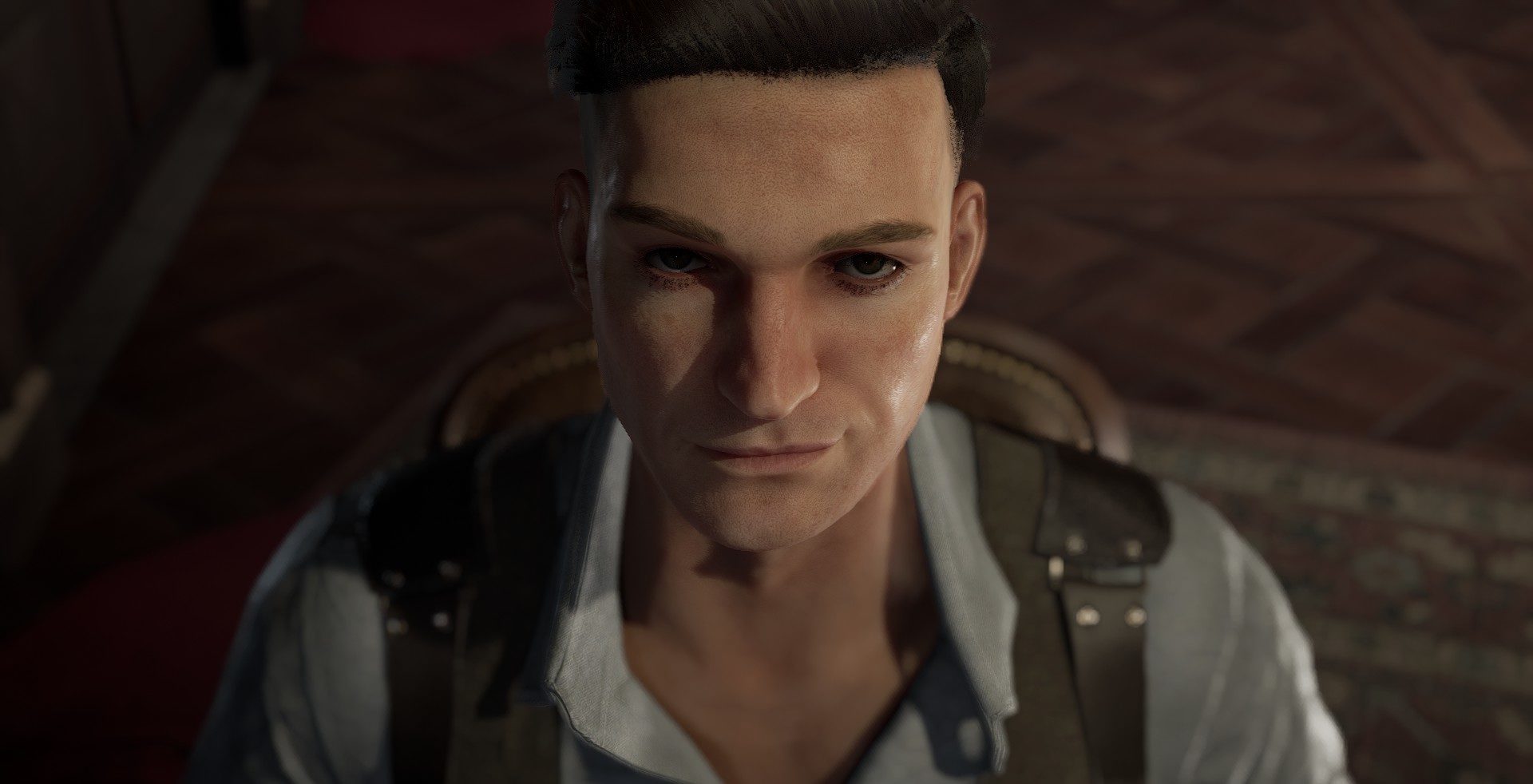

Oh and never let it be said that this game is not beautiful, the cutscenes, the characters, the places; they’re all gorgeous. I’ve been colloquially referring to this game as “Sherlock Holmes: Oh No He’s Hot” for a reason.

Golden guy

Sherlock Holmes: Chapter One isn’t shy to iterate on old ideas though. I love the approach to portraying Sherlock and his partner Jon. The relationship is unlike other versions I have seen, but I will avoid detail that may spoil things. The result, however, contrasts with the common interpretation these days. The stereotypical Watson and Holmes duo has trended toward hostility. Watson is the “normal one” being angry at Holmes for blowing up something for a scientific experiment.

This pair’s relationship is, by comparison, amicable. This Sherlock, still in his youth, is insecure. His immature morality sees the truth as an absolute good; pursuing it is imperative. This absolutism can cause friction with others, so Jon helps by sanding off the rough edges. Jon will request Sherlock do little tasks, such as giving medical care to bystanders. The interplay feels like two bickering friends; they rib each other, but there is a genuine love there. As the story progresses, the tensions in the narrative marry well with the relationship. The pair meet a gallery of other characters, suspects, victims, witnesses and bystanders alike.

Each relationship brought in has a suitable weight. Outside of the classic pair, Mycroft, Sherlock’s rather paternal older brother enters some tension into proceedings. However, Verner Vogel, another Frogware’s original has a bit more sway on the main quest. As a character, he is a bit of an enigma, with unknown ties to the miasmic past Sherlock is pursuing. A figure of interest, and a fascinating counterpoint to Sherlock’s stringent world views.

I’ll give praise to Sherlock Holmes: Chapter One for its buffet of crimes to solve. There is a tiered system at play here. The big mystery surrounding Violet Holmes, and the goings-on of the manor, spans the entire game. It is at the top of the pyramid. Below are the four “main cases”, each spanning an hour or two. The bottom level is the dozens of side cases. These vary from a five-minute lore flashback to a three-part treasure hunt that soaked up hours. We’ll discuss all, but I want to commend the tiers of tasks. If you have time for a 15-minute session, you can knock over another quest.

Dr. Know

Before we talk about the mysteries, let’s talk about mystery-solving. Sherlock Holmes mythos focuses on the detective’s mind; Frogwares sculpts gameplay around his perspective. As you walk around Cordona, clicking on items of interest allows a closer examination and evidence collection. They may become items to use on other items to progress, a standard of point and click games, but Sherlock Holmes: Chapter One has nuance. Examination of evidence, and suspects, plays a larger role. New points and persons of interest can be pored over. Nevertheless, the game forgoes a physical inventory for the case file system which functions as a cerebral database.

” Frogwares have made a dozen of these games, and you don’t put that volume of work into a single series without learning how to polish.”

The Case File system pulls double duty as a to-do list and journal. For mystery games, this is a must-have. It’s easy to load a save file and resume or pick up the trail of a different case. Chapter One pushes these standards further. I’d like to exalt one amenity as an example: case-by-case waypoints. It’s a minor addition: case file items can be used as map markers, and only reveal while that case is active. Tying items to locations and having only those in the active case visible make the experience butter smooth. Frogwares have made a dozen of these games, and you don’t put that volume of work into a single series without learning how to polish.

This raises a question: If there are no inventory puzzles, what is there to do? Well, Sherlock Holmes: Chapter One has an odd method to move evidence into the social sphere: pinned evidence. It’s not bad, per se, but it took some time to grasp the idea, and how pervasive it is. By holding a piece of evidence in mind, such as the knowledge that someone left a trail of blood, you can use abilities, in this case, your concentration (i.e. Sherlock’s Detective Vision), to track them. There is a solid palette of investigating mechanics, including navigating the world. There are no objective markers in Sherlock Holmes. It’s the player’s job to read the address and pinpoint it on the map. Like most mechanics, it’s a smart idea but may feel a touch stale by the end.

Social interaction, in part due to pinning, feels weird. If you need to find a building, you may be able to use the archives. Other times, asking around is the only way. I appreciate that NPCs are not mere set dressing. Granted the compromise is each character has a pool of stock response in stock “rich” or “criminal” or “policeman” responses. They boil down to “I will help you”, “I don’t know about that” (if you ask the wrong type) or “I refuse to help you because you are [rich/poor/a criminal etc.]”. Addressing the latter, Sherlock can disguise himself. Switching up outfits, headwear, eyewear and makeup will change up your disguise stats. The stats indicate how favourable you are to Cordona’s demographics: upper class, Cordona local, police officer, solider/sailor, worker, hobo/criminal. I’ll highlight again the race thing, as disguises sometime come with weird accents. Your mileage may vary on whether it’s tasteless; I didn’t love it but doing little disguises and such is somewhat part of the canon. Again, this is a nice system, though it can be less fun over time as you are constantly removing your stylish ensemble.

For the big cases, Sherlock forms theories in the mind palace. Through the investigation, facts appear; alibis are broken, motives emerge, coincidences present themselves. However, to form a theory requires multiple threads tying them together. The Mind Palace serves this purpose. Look at the pile of clues, find two that relate, be it a contradiction, or a common thread. This creates a node on the mind map, which explains the connection. One wrinkle is what I’ll call the “split nodes” where our theme of judgement and truth appears. These nodes offer two interpretations. For example, a suspect’s alibi was an hour spent at the bar away from his wife, the victim, but patrons saw him for only 30 minutes. This leaves two options for those two 30 minute windows, one for the suspect to kill, the other for the third party to murder, while the husband is away. Your judgement (which can be changed), will affect possible suspects to accuse. Furthermore, a final choice typically should police punish a culprit, is left to your discretion. Yet, for there is no tangible consequence; the developers don’t tell you if you are right or wrong.

The main cases themselves are an entertaining little series of confounding murders and a heist. With each case more of the manor opens up, which in turn deepens the overarching mystery. Whilst I like this as a game idea, it feels a little “video gamey”, for want of a better term. It just feels contrived that after the initial case the main storyline constantly starts at the manor, and in time loops back to it. The looping style does feel like a good choice, after all having a smaller space for the emotional turbulence helps its potency. This aside, surely the game could have handled things a little more naturally.

Contrivance to kill

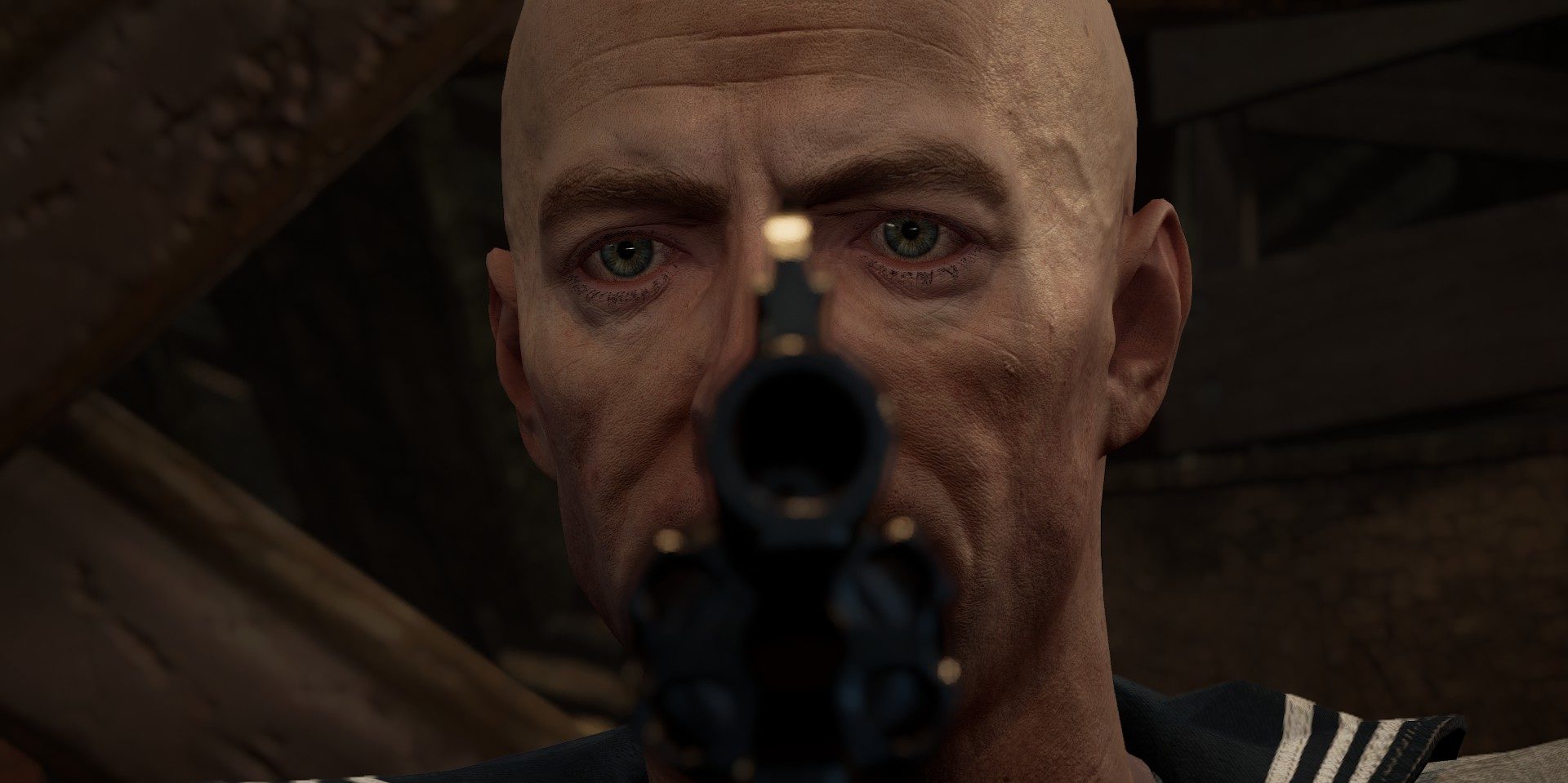

I adore these unique mechanics, which makes the combat all the worse in comparison. AAA mysteries have taught me that combat and mysteries make a clumsy marriage. Fighting feels like an “insert drama here” diversion from the investigation. Sherlock Holmes: Chapter One has not convinced me otherwise. The developers are self-aware at least; a difficulty option lets you skip combat entirely.

The combat portion of gameplay does a lot to bring a unique style, thankfully. Aiming comes with limited bullet-time on a cooldown. It’s a necessity; combat demands high accuracy to shoot off the armour. Unarmoured enemies can be stunned by hitting an environmental object (e.g. a bag of flour) or character item (e.g. a bottle of flammable liquid). Then a QTE is all that’s left to knock out the combatants. It’s playing off the “Sherlock is smart – they can do 4D Chess-fu” trope the great detective has accrued over time. In theory, I appreciate this. In practice, less so.

To make players feel like a badass sharpshooter, it needs to feel hard to pull off. The flipside is that it is easy to screw up. Similarly, we could say that Sherlock Holmes: Chapter One misses the mark. Enemies may have movements and behaviours, like moving their body between my gun and the armour, which can throw things off. You can get a few body shots before the suspect dies. Conversely, shooting off masks and hats is dangerous; headshots are one-hit kills. It can suddenly stop being fun and start being annoying and restrictive. However, the infuriating part is the moralisation of it all.

“Shoot an assailant dead, and Jon starts handwringing about killing people whilst in life-or-death combat.”

“Your morals are your own choice”, the game states; at the same time, it will berate you for misbehaviour. This crosses all kinds of situations, primarily through Jon’s diary. Fail an archive search, or a crime scene recreation multiple times, and Jon will berate you. Fail at asking NPCs for info, Jon will berate you. This isn’t even a moral issue, more like Jon just whining like a child tortured with boredom or something.

The ones that do carry moral weight are no better. Shoot an assailant dead, and Jon starts handwringing about killing people whilst in life-or-death combat. “He’s a little callous but cold-blooded murder?!” Jon will cry.

Oh but the big case moments are much worse. Villains prattle that “you are no better than I, dear Sherlock!”, comparing my fight kill count of one, to their intention to publicly execute the whole group. My personal favourite was a particular big case. 20 minutes spent researching, disguises, conversations with agents; top-shelf espionage all around. I found my location, cleared out the henchmen, leaving only the head honcho. Shot by shot, pieces of armour littered the chest-high arena, leaving only the helmet. However, as my shot raced towards it, the big boss, turned his head briefly. It is from this butterfly flapping its wings, the entire case crumbled, and a chorus of “I can’t believe you would shoot this person, what’s wrong with you?” came courtesy of Jon and the quest giver soon after.

On her majesty’s secret services

At the risk of sounding egotistical, I do like the positive notes from Jon. However, I’d contend that I enjoy this because it required overcoming something. Jon’s challenges, for example, are simple tasks like finding 3 books or solving a puzzle. It’s a nice touch that rewards a little exploration or following a certain rule. It is one of the elements that make the gameplay a bit fun when separated from the main campaign trail.

The remaining side quests are where the gameplay shines. My favourite is the coin quests. Sherlock finds that his coin collection stolen, the coins hidden across Cordona by his brother Mycroft. At the locations marked on the map is a clue that refers to Mycroft’s past cases on the island, which lead to the coin. These are navigational puzzles, my first time with this type of puzzle. The puzzles are rather straightforward. One for example describes a murder on a nearby street, with the shot coming from the northwest, from somewhere high. Standing where the victim died, it’s easy to find where the shooter was located, a key piece of information to then find the coin.

Another task is the treasure quest, enjoyable but more taxing. The task is simple, but not easy. The island is littered with little treasure trunks. To find them, your only clue is a photograph of the surrounding area. This challenge demonstrates how well-designed Cordona is. Attention to detail is a necessity to latch onto any clues the photos have to offer. The buildings are white, which means a central district. Stones on the ground mean Old City, or maybe Silverton or Miner’s End if there’s grass around, that kind of thing. Even then, finishing this challenge was an immense task, spanning hours, chasing red-herrings and running in circles. The trade-off for an open-ended challenge like this, you lose control of how quickly a player can move through it.

It’s worth considering this tension. On the one hand, I enjoy the challenge of these side quests, but I prefer the main quest narrative to go without gameplay friction. The problem is it leads to a game that can have a satisfying narrative and satisfying gameplay but with little intersection.

“You can expect both a well-presented story and satisfying gameplay challenges, but not at the same time.”

The main cases feel too easy. Granted there are difficulty settings, but they merely remove user conveniences like interaction icons or “key evidence collected” alerts. I don’t think this is more of a challenge, but more opportunities to get lost. On occasion, you must present evidence to back up accusations, a nice, if daunting, task to be sprung upon you. Otherwise, I’d rarely stumble at any point in the cases. If anything, I’d miss something because I’d take some things as obvious. If, say, I examine a case with a gun-shaped outline, I would assume examining the brand on the front of a gun brand, confirming that it is, in fact, a gun case, would be unneeded. Otherwise, the only error would be interpreting ambiguous elements in ways other than prescribed by the developer. With enough practice using the pinned evidence system, it resolves most of the challenges out of the gameplay.

The result is the main story that feels more like Life is Strange than Cluedo. I just didn’t feel as great a sense of achievement or drama when the final curtain was falling. The focus is more on thinking about the circumstance, giving a judgement and telling a well-paced story. It all leads to the choices, and in time, their consequences. With those priorities in mind, it’s best to avoid taking too large a backswing. It’s telling how the game uses the trope of “mental blocks” to portion out its narrative and sell the rebuilding and clean out the house of your past as a metaphor. Stonewood Manor becomes the place where all cases begin and end, a small, enclosed space instead of a giant island. But it betrays the central tension of Sherlock Holmes: Chapter One. The game is split. In the main quests the story is the star; gameplay along for the ride. In certain pockets the reverse is true. In short, you can expect both a well-presented story and satisfying gameplay challenges, but not at the same time.

8

Great

Positive:

- Well-presented story with interesting cases

- Jon and Sherlock's relationship is fantastic

- Cordona is a beautiful and functional locale

- Side cases make for some unique gameplay

Negative:

- Satisfying gameplay and storytelling rarely intersect

- The combat is a cute idea but annoying to play

Despite some rough edges, Sherlock Holmes: Chapter One has its heart in the right place. Frogwares is taking the classic Sherlock mythos and spinning off some impressive original work here. The story is well-presented, with the partnership between Sherlock and Jon particularly pleasant. Other cases show some interesting new puzzle types that I have not yet seen before. Whilst the two strengths of this title are separate, which annoys me somewhat, it’s the annoyance I feel when a game is a few decisions short of me showering it in unqualified praise. As it stands, Sherlock Holmes: Chapter One is a standard-setter for open-world mystery games.