Platforms:

Xbox One, PC, Xbox Series X|S

Released:

November 15, 2022

Publisher:

Xbox Game Studios

Developer:

Obsidian Entertainment

“The revelations we experience can be terrifying to us and to those who witness us experiencing them.”

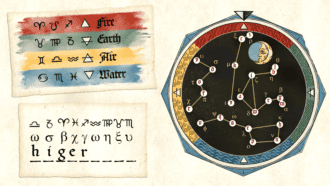

During my first few hours with Pentiment, I kept thinking, “this is a game for lit nerds.” By which I meant nerds of literature, art, history, mythology, geography, and similar fields I know very little about. Look at any screenshot, you can tell the game looks like a medieval painting. The music is period-appropriate, and character dialogue boxes reference different methods of calligraphy. But beyond its appearance, the game is all about how people treated each other in 1518, depending on factors such as wealth, gender, race, and most importantly, belief. Pentiment is a narrative adventure full of difficult choices, tense reveals, and intricate characters, presented through some of the best writing I’ve seen in a game.

I went into Pentiment expecting a campy medieval time management sim, but what I got was an experience mechanically closer to Night in the Woods, but set amidst semi-realistic historical events. Pentiment takes place in 1518 AD Bavaria, across a small farming town named Tassing and the nearby Kiersau Abbey, a monastery occupied by Christian nuns and priests. You play as Andreas Maler, a young artist from Nuremberg, staying in town while working on a commission at the abbey.

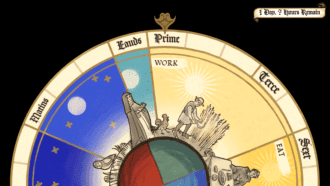

Andreas is new to Tassing and isn’t there for long, and his unique position means he is of equal standing in both the town and the abbey in charge of it. Each in-game day is separated into segments of time, each segment letting you explore most every room and house and talk to everyone you meet. Once you choose an activity that takes time, the game will transition to the next part of the day, where the cycle continues again. Early on, a shocking event rocks this quiet countryside community, and as a benevolent outsider Andreas takes it upon himself to find whodunit, which means getting to know everyone is crucial.

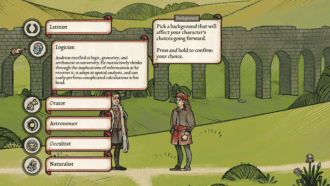

Andreas isn’t quite a blank slate, but the game gives you a lot of choice in developing him, which is appropriate since the game is made by Obsidian Entertainment. Pentiment isn’t nearly as customisable as Pillars of Eternity, but you still get to choose facets of Andreas’ life, such as what he studied at school, and where he likes to travel. These choices directly influence the dialogue options you get, of which there are many. Aside from choosing Andreas’ interests and knowledge, the dialogue options also let you finetune his personality. Is Andreas a well-meaning outsider who cares for others, or is he a rich jerk who loves butting into other people’s business? You can make him witty and charismatic, or to have jokes fly right over his head.

Each of Pentiment’s several dozen characters is fully fleshed out, their wants and needs are clear and distinct, and each of them is hiding some kind of secret or shame that they aren’t going to easily divulge. Even though you have lots of choice over Andreas’ background and dialogue options, Pentiment smartly teaches you that this doesn’t mean you can control how others see him. As much as I tried to play Andreas as a loveable goodie two-shoes, my choices would sometimes annoy or severely offend people when I didn’t intend to, which made me think about how I treat people in real life.

Even the most insignificant choices you make could end up being important. Another RPG-ish element the game employs is a success check that pops up during pivotal, nail-biting moments, that show you in detail every previous choice you made that led up to what’s happening in the present. It’s a brilliant way to heighten tension, and to highlight how you reached this moment thanks to the choices you made, for better or worse.

Every conversation, even those tangential to the main plot, is fantastically written, discussing societal issues of the time and region, but focusing on character relationships first and foremost. An Ethiopian priest visiting the abbey is eager to make new friends, but along the way explains that there were lots of people of colour in Europe during medieval times, something other game developers seem to forget for some reason. And for a game that’s 90% dialogue, Pentiment frequently doles out palate-cleansing, once-off minigames and setpieces. For example, a seemingly mundane conversation about books turns into a surreal sequence in which you travel into a book and walk around its pages.

I’m hesitant to say any more about Pentiment’s narrative than I already have, since I was surprised by a lot of the narrative beats – in fact, I would argue that some of the game’s marketing spoils too much already. But one thing I think deserves a mention is how unexpectedly long the game is. There were several points where I thought the story had arrived at a conclusion, and then it kept going, introducing new characters and dramas to Tassing, gently reminding me that there was more to learn. Pentiment makes full use of its runtime, leading you towards its beautiful ending.

“Is Andreas a well-meaning outsider who cares for others, or is he a rich jerk who loves butting into other people’s business?”

Every time you meet a new character, their profile is recorded in the menu, which is very handy to keep track of who’s related to who. Similarly, I appreciated the glossary which takes notes of all the terms that may be unfamiliar to players like me who weren’t alive in the 1500s, like the specific names they had for various times of day. As useful as these menus are, they are unfortunately fairly cumbersome. They are too slow to navigate, which makes it clunky to sort through the large volume of profiles and terms you accrue in the first few hours alone. It’s also not possible to pull these menus up during conversations, which I wished for during long stretches of dialogue with lots of new words. These issues didn’t hinder my overall enjoyment of the game, but upset my instinct to be a completionist, even though I admit Pentiment may not have been designed to be played that way.

Another issue I encountered were not-infrequent crashes throughout the game, mostly when I was trying to Quick Resume on my Xbox, but occasionally during gameplay as well. As unwelcome as the crashes were, I never actually lost progress thanks to the game’s diligent autosave system. Still, the crashes aren’t great.

As mentioned earlier, the game’s aesthetics showcase a tremendous attention to detail. Despite its medieval art style, each character is capable of showing a range of emotions, and are minutely animated, such as when a frail old man gets up off a stool. Dialogue boxes are laid out like words etched on parchment, complete with spelling mistakes being crossed out and corrected, and highlighted words being written after the rest of the sentence. Characters show different kinds of handwriting depending on their personality, social class, or their relationship with Andreas. Some fonts are inscrutable, so there’s a helpful toggle in the settings to make the fonts easier to read, and another toggle to turn on the medial s, which marks the first time I had to Google a term I didn’t recognise in a game’s settings menu.

9

Amazing

Positive:

- Excellent story

- A deeply customisable protagonist

- Well written characters

- Detailed, gorgeous art and animations

- Your choices shape the story

Negative:

- Cumbersome menus

- Repeated crashes

Pentiment is a remarkable achievement in storytelling. If I were to play again and make different choices I’m sure I would discover new dimensions to these characters I’ve come to know very well. Thanks to the game’s aesthetics, its meticulously researched writing, and the pedigree of its development team, the story of Andreas Maler is well worth experiencing. The game gracefully balances serious themes, soap operatic twists, and some very funny moments, revolving around a large cast of diverse, complex characters. Obsidian may have taken a risk making a game so unlike anything else they’ve made before, but the gamble has well and truly paid off. It’s not just a game for lit nerds.